March 2016 marks the 25th anniversary of Atelier Viollet’s residence in its current address, 505 Driggs Avenue, Williamsburg, Brooklyn. In commemoration, the workshop wishes to share a bit of the history and development of Atelier Viollet.

Atelier Viollet studio, 2016.

Atelier Viollet was originally located on Metropolitan Avenue between Lorimer and Union. Beginning around 1985, Jean-Paul Viollet ran his shop in a roughly 4,000 square feet space shared with two other people who used their portions as personal studios. From this busy environment he was able to produce his first works of furniture. Approached by real estate agents in 1991 with the offer of the empty warehouse that now houses Atelier Viollet, Jean-Paul made a bold investment that has since proved its worth.

After crucial renovation and expansion, the workshop transformed into a space that would properly accommodate the necessary machinery and staff. In the beginning, the team consisted only of Jean-Paul and three other craftsmen. The location was ideal as it was in close proximity to Manhattan via the Williamsburg Bridge or the L train, yet thoroughly removed from its constant activity. The neighborhood was heavily industrial at the time, occupied mostly by warehouses storing various resources such as glass, metal, and lumber. Bedford Avenue was a more subdued residential area animated mostly by locally-run Polish or Italian bakeries. An active creative community composed of artists and artisans existed harmoniously with local residents. I’m shocked Williamsburg didn’t change sooner. It made so much sense, Jean-Paul confesses.

Expansion of Atelier Viollet, c. 1992.

Delivery of Atelier Viollet equipment on Driggs Avenue, c. 1992.

Jean-Paul’s plan was to customize a space that could sufficiently house a showroom, an office area, storage space, and multiple workrooms separated by technique and process stage. Early on, Jean-Paul attended auctions to purchase barely used equipment that would soon fill his workshop. Although he has since updated his inventory, many machines remain the same. Clients rarely came to the workshop as it was still considered “too far” from Manhattan, yet more projects began to enter the workshop doors. With designated areas for fabrication, joinery, and finishing, there was gradual improvement in the expertise at which the pieces were being constructed. Perhaps the isolation from Manhattan and additional space fueled an interest in experimentation because Jean-Paul and his team began to explore the possibilities of exotic materials and the application of patina on various metals. His use of textured shagreen and shimmering veneers drew early attention to his work. This exploration came out of an interest in accessing new end results and products as opposed to remaining confined to old procedures.

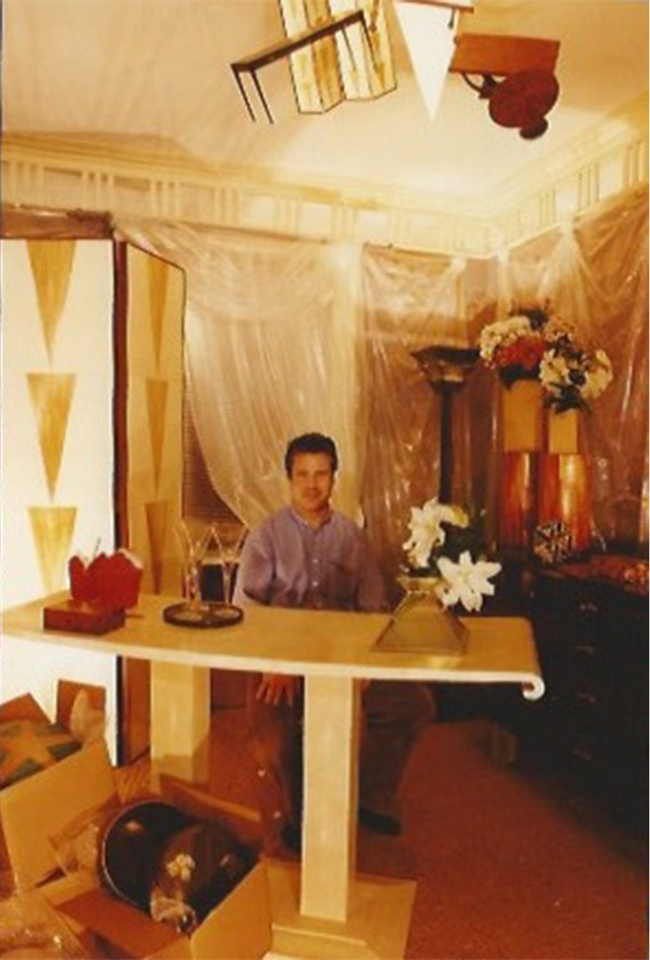

Jean-Paul surrounded by selected pieces for the French Designer Showhouse, 1993.

Jean-Paul emerges as the seventh generation of Viollets working with wood, dating back to his great-great-great-great-grandfather, Pierre Violet, who was also a woodworker in his hometown of Seyssel, France in the late 1700s. The tradition had been passed down from father to son ever since. However, Jean-Paul wished to establish a more orderly woodworking shop than his father’s. He explains that even though his father, Paul Viollet, was equally creative in his own right, he was stuck with woodworking. Paul had vision and worked hard, but did not establish a direction in which his work could evolve. In possession of maps and sketches designed by his father and grandfather, Jean-Paul sought to reinvent what he had learned surrounded by the trade.

Jean-Paul’s father, Paul Viollet, standing outside of Atelier Viollet, 1993.

Despite this urge for innovation and experimentation, Jean-Paul maintains to this day that he holds onto traditional designs and techniques. It is this foundation that would propel his future development. Hard work was always mandatory, he explains, you always had to do the best that you could, and no less. This seems to echo throughout Atelier Viollet’s trajectory. He hoped that holding onto tradition would allow him to simultaneously push his materials to create something modern.

This attachment to family practice continues with his wife’s introduction to the straw marquetry. Sandrine Viollet was initially exposed to a project that required the craft with no formal training. Upon familiarizing herself with the material’s characteristics and completing the first project, she began to take on more. She was fascinated by the materials seemingly simplistic nature that activated once manipulated into new forms and colors applied to varying furniture surfaces. The learning process consisted of discovering efficient dying, trimming, and application processes. In addition, she studied the proper orientations in order to achieve a balanced and aesthetically-pleasing luminosity. Soon, straw decorated boxes, screens, tables, and walls. The demand for straw-based commissions blossomed, emphasizing the growing interest in the rare iridescent material.

Jean-Paul and Sandrine Viollet pose with prototypes, 1993.

As new projects and techniques evolved, so did the workshop. The team grew, consisting of nine members today, including its founder.Their dedication and skilled precision aligns itself with the Atelier Viollet history and philosophy. The persistent effort declares itself with the intricate sophistication found in each project. The clientele also expanded (many more now visit the shop) as did the shop’s recognition with featured work in many furniture and design magazines. Jean-Paul declares vision and organization as cornerstones to success. He explains, If you have a goal, you build towards it step by step. To me, organization is efficiency. When you work with your hands, you need to. It’s already very difficult to work with your hands. This balanced relationship between hard labor and experimental creativity manifests itself in Atelier Viollet’s expansive oeuvre. In addition, a careful attention to history, that of the Viollet family as well as Williamsburg, have equally played an integral role in nurturing the Atelier’s growth. Jean-Paul closes, We are proud to have arrived at a time pre-gentrification and proud to still be here as artisans. There is very little life of the old neighborhood left, it’s almost gone. The group of artists and artisans that once populated the area (along with many locals) have been forced to leave due to the area’s real estate boom. It’s difficult to conduct such a business today because you are constantly pressured by real estate and insurance rates. We want to preserve the spirit of the old community; of tradition; of styles past, present, and future.